There is a pond in the county where I live that used to be a real hot spot for birds and other wildlife. The dairy farm fields around it had lots of native vegetation, which was very welcoming to avian wildlife.

There is a pond in the county where I live that used to be a real hot spot for birds and other wildlife. The dairy farm fields around it had lots of native vegetation, which was very welcoming to avian wildlife.

A couple years ago, the farmers retired, and the property was purchased by a vineyard owner to expand his holdings. He cut down most of the vegetation around the pond and along the road bordering the fields. He has turned most of the fields into vineyards, keeping only small portions untouched where birds can still find some refuge.

A couple years ago, the farmers retired, and the property was purchased by a vineyard owner to expand his holdings. He cut down most of the vegetation around the pond and along the road bordering the fields. He has turned most of the fields into vineyards, keeping only small portions untouched where birds can still find some refuge.

I used to see a yellow-billed cuckoo return from migration to a small patch of trees there every spring. This now is a thing of the past. However, some pond-edge vegetation had been regenerated, and a little bit was planted, so some birds are hanging in there. They still make for some interesting birding. Here is what I saw on a recent visit.

The largest birds that keep returning to the pond are the great blue herons. Sometimes there is one; other times there are two or three. Occasionally a green heron flies in or over but none stopped by on this occasion.

The largest birds that keep returning to the pond are the great blue herons. Sometimes there is one; other times there are two or three. Occasionally a green heron flies in or over but none stopped by on this occasion.

The heron often has good days fishing there. I often see him/her snag at least one fish and often more than one.

The heron often has good days fishing there. I often see him/her snag at least one fish and often more than one.

The heron stalks along the pond and frequently flies across to the other side for a change of venue. Perhaps the fish manage to hide well once they realize s/he is stalking them.

The heron stalks along the pond and frequently flies across to the other side for a change of venue. Perhaps the fish manage to hide well once they realize s/he is stalking them.

It’s wonderful to see the heron’s wings spread as the bird alights and then begins stalking again.

Eastern bluebirds had taken advantage of an electrical installation next to the pond (which also serves as a resource for the local fire department as needed). They not only used it as a perch for bug seeking but also built a nest inside it. I wondered what the new owner would do.

Eastern bluebirds had taken advantage of an electrical installation next to the pond (which also serves as a resource for the local fire department as needed). They not only used it as a perch for bug seeking but also built a nest inside it. I wondered what the new owner would do.

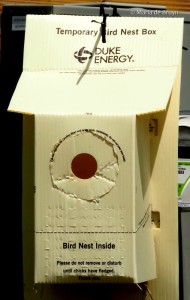

To my great surprise, his problem was solved by the local electricity company. They removed the birds’ original nest and put it into a temporary nest box!

Mom and Dad bluebird were guarding the nest space, but it looked like they were still getting used to the new digs.

While watching the bluebirds, I suddenly heard a commotion in front of me, but I couldn’t see what was happening behind the bushes at the pond’s edge (I’m short!). However, I could tell that a bird was in distress. I wondered if one of the huge snapping turtles had caught a duckling. I walked further along and saw one of the two resident female wood ducks (above) swimming away from the area.

While watching the bluebirds, I suddenly heard a commotion in front of me, but I couldn’t see what was happening behind the bushes at the pond’s edge (I’m short!). However, I could tell that a bird was in distress. I wondered if one of the huge snapping turtles had caught a duckling. I walked further along and saw one of the two resident female wood ducks (above) swimming away from the area.

No ducklings followed and I feared the worst. One mother had five ducklings (above) while the one swimming away had lost one a few weeks before. Now I wondered if she had lost others, too. Luckily, I later saw her return to the area and shepherd four ducklings across the water to the other side.

No ducklings followed and I feared the worst. One mother had five ducklings (above) while the one swimming away had lost one a few weeks before. Now I wondered if she had lost others, too. Luckily, I later saw her return to the area and shepherd four ducklings across the water to the other side.

In the small bit of meadow immediately adjacent to the pond, red-winged blackbirds are now nesting. One pair has a nest close to the road and they are warning visitors away with constant flights along the pond’s edge, while the male calls repeatedly.

The female was taking breaks from warning-off flights to enjoy an occasional meal, at this time consisting of one of the remaining periodical cicadas that emerged recently.

She wasn’t the only one seeking these insect delicacies. Two Northern mockingbirds were also intently examining the area under a tree for them. One finally had success in snagging a cicada. (For more about the cicadas, see my previous two blogs!)

The male red-winged blackbird was very busy keeping “intruders” as far as away as possible from their nest. He warned off the great blue heron, who was actually pretty far away. (He is flying away from the heron on the left side of the photo.)

He also went after a red-tailed hawk, who appeared soaring overhead.

He also went after a red-tailed hawk, who appeared soaring overhead.

Common grackles, often present at this pond, will also chase away these hawks. There weren’t any around to join in the foray this time, but the photos below taken at another pond show how they go after the red-tails.

I looked at a small patch of chicory across the road to see if any bobolinks, grosbeaks or meadowlarks were around. I love this plant and planted some seeds in my own yard, hoping to attract more pollinators and birds. So far, they have not sprouted.

Below you see a young blue grosbeak and a pair of Eastern meadowlarks who were in the patchy field spots another time.

Usually, several types of swallows frequent the pond, including purple martins, tree swallows, barn swallows and Northern rough-winged swallows. I only saw a couple of the latter this day and only got poor flight photos as my camera began acting up, refusing to focus.

Staring hard across the pond, I did manage to spot three killdeer, four least sandpipers and a couple other sandpipers that I couldn’t immediately identify. I later learned that they were semipalmated sandpipers, which I hadn’t seen there yet. (If you click on the photo, you see it larger; then go back to the blog.)

That hour at the pond didn’t turn out to be a super one for capturing stellar photos, but it was definitely a great one for relaxing, observing the action and appreciating nature again!