This was not a planned blog, but I recently observed something that simultaneously intrigued, amazed and astounded me, so I wanted to share it with those of you who may not have witnessed this either.

Like many gardens in my neighborhood, my yard has its fair share of leopard slugs (Limax maximus), but they don’t bother me as they do some other people who complain about them eating their vegetables. Until recently, I never thought about the slugs much and certainly didn’t wonder about their life cycle. Then my friend Mary posted a lovely photo of two intertwined leopard slugs mating and my interest and curiosity were piqued.

Like many gardens in my neighborhood, my yard has its fair share of leopard slugs (Limax maximus), but they don’t bother me as they do some other people who complain about them eating their vegetables. Until recently, I never thought about the slugs much and certainly didn’t wonder about their life cycle. Then my friend Mary posted a lovely photo of two intertwined leopard slugs mating and my interest and curiosity were piqued.

A few days later, a fellow nature lover, Ace, reported that he had a cool photo to show me – and there on his iPhone was a photo of mating leopard slugs. It turns out that their anatomy makes for a somewhat bizarre spectacle – at least to a human being if not a fellow slug. Now I really wanted to see this phenomenon, too, and I followed Ace’s recommendation, going out into my yard at night with a flashlight to see if I could find some amorous mollusks. Lo and behold – as I rounded the corner of my house, there were three pairs of large slugs getting ready to reproduce! They were leaving glistening slime trails on the brick wall as they slowly got into position.

A few days later, a fellow nature lover, Ace, reported that he had a cool photo to show me – and there on his iPhone was a photo of mating leopard slugs. It turns out that their anatomy makes for a somewhat bizarre spectacle – at least to a human being if not a fellow slug. Now I really wanted to see this phenomenon, too, and I followed Ace’s recommendation, going out into my yard at night with a flashlight to see if I could find some amorous mollusks. Lo and behold – as I rounded the corner of my house, there were three pairs of large slugs getting ready to reproduce! They were leaving glistening slime trails on the brick wall as they slowly got into position.

The slime that the slugs exude has multiple purposes – they can leave a trail behind them as a signpost to the way home, they can numb the mouth of a potential predator with the mucus as a means of defense, and they can broadcast their interest in some reproductive behavior by emitting pheromones to attract a potential mate.

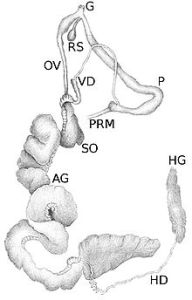

They don’t actually need to mate to reproduce – each slug is a hermaphrodite and can fertilize its own eggs with no need of outside assistance. Slugs have an organ called a spermoviduct (SO), which has two parts – one for the sperm (vas deferens, VD) and one for the ova (oviduct, OV), as seen as this drawing from the Wikipedia page.

They don’t actually need to mate to reproduce – each slug is a hermaphrodite and can fertilize its own eggs with no need of outside assistance. Slugs have an organ called a spermoviduct (SO), which has two parts – one for the sperm (vas deferens, VD) and one for the ova (oviduct, OV), as seen as this drawing from the Wikipedia page.

Some slugs apparently like reproductive acrobatics, however, and seek out a partner. The mating begins with a pair of slugs following one another around and nudging and licking one another. (A couple photos look browner – I took those with a flash but most were taken with one hand holding a small camera and the other shining a flashlight near the slugs.)

They then begin to curl up together and suspend themselves from a long mucus rope, which is somewhat stronger than the slime that they usually exude. They form a kind of writhing ball as they intertwine their elongated bodies (see this video for an example).

Next comes the awesomely weird part – out of a gonopore on the right side of their heads (the elongated tentacles are for vision) come their translucent mating organs (penises)! This video, which is shown in a horizontal position, lets you see how this happens.

Wouldn’t this interesting anatomy and reproductive behavior make an interesting plotline for an SF novel about a genderless society?

Because the slugs are hanging upside down, gravity helps pull down their reproductive organs, which are pumped full of body fluids until they are as long as the slugs’ entire bodies! Their penises are everted (turned inside out) and the two mollusks intertwine these just like their bodies. They take a while to exchange spermatophores as the penises twirl, intertwine, elongate and pull back to look a bit like a chandelier.

When the creatures have been joined at the neck for some time, they begin to slowly withdraw their reproductive organs, which are now carrying genes from another parent.

After they separate, one of the pair usually consumes the mucus rope from which they dangled in love as it carries extra nutrients which they can use after their vigorous efforts.

Each slug may spend some time examining its gonopore (above) – and perhaps they are helping push back in the penis when they do this, too. After watching the process for two pairs of slugs, I decided to give the third pair some privacy during their mating tryst. On the wall beneath my screened porch, I discovered another slug with a mucus rope dangling from its tail – leaving me with a little mystery as to why this might have happened. A partner slug was not in evidence except for a much smaller slug – perhaps the big one tried to mate but the younger one was not ready. These mollusks with a life span of 2.5-3 years don’t become sexually mature until they are 2 years old.

I do know that at least three and perhaps six slugs will each be laying up to 200 eggs somewhere in the yard. And when I see them in the future, I will undoubtedly always be picturing them in my head doing their dangling dance with intertwined translucent blue tubes that will help promote their future generations. My discovery of their life cycle has also reinforced my support for scientist Hope Jahren’s (Lab Girl) observation: “…being able to derive happiness from discovery is a recipe for a beautiful life.”